The story of Wellington

T2905's Last Flight

Wellington T2905 (a Vickers Armstrong Wellington mk 1C) came into service on 27th October 1940 and was transferred from 24 Maintenance Unit to No 11 Operational Training Unit, which was at that time stationed at RAF Bassingbourn, Cambridge, on 22nd February 1941 (see the planes Movement Sheet*). For more information about the formation of 11 OTU see http://www.rafweb.org/OTU_1.htm.

Mk 1C Wellingtons had the following specifications:-

| Engines - Two Bristol Pegsus XVIII | Armament - 6 x 0.303in guns |

| Dimensions - Span 86ft 2in (26.26m) | Bomb load - 4,500lb (20000kg) |

| Length - 64ft 7in (19.68m) | First flight - 23 December 1937 |

| Max speed - 235mph (376km/h) | Number built - 2,685 |

| Ceiling -18,000ft (5,454m) |

The crew were in No's 28 and 29 groups of 11 OTU. They were all undergoing training and on Wednesday 30th April 1941 they took off in Wellington T2905 on a night flying exercise. According to a letter from the RAF to my uncle they were supposed to fly to Andover, make a turn and fly to Sharpness at the head of the Bristol Channel. It is unclear what they were to do there. The letter mentions that they had practice bombs on board. These were usually bomb casings full of inert material, such as sand and contained a 'spotting charge', which was a small amount of explosive that would detonate upon impact so that targeting accuracy could be determined. The plane also would have carried 4½" recognisance flares. These would be dropped just after the practice bombs and would illuminate the target so that photographs of the spotting charge explosions could be taken in order to prove the accuracy of the bombing run. It is possible that they were flying to a practice range to drop these bombs, although the pilot does not remember anything about this. It is also possible that they were flying with these practice bombs on board in order to simulate the weight of real bombs as the plane would have performed differently when fully loaded than when empty.

The crew were in No's 28 and 29 groups of 11 OTU. They were all undergoing training and on Wednesday 30th April 1941 they took off in Wellington T2905 on a night flying exercise. According to a letter from the RAF to my uncle they were supposed to fly to Andover, make a turn and fly to Sharpness at the head of the Bristol Channel. It is unclear what they were to do there. The letter mentions that they had practice bombs on board. These were usually bomb casings full of inert material, such as sand and contained a 'spotting charge', which was a small amount of explosive that would detonate upon impact so that targeting accuracy could be determined. The plane also would have carried 4½" recognisance flares. These would be dropped just after the practice bombs and would illuminate the target so that photographs of the spotting charge explosions could be taken in order to prove the accuracy of the bombing run. It is possible that they were flying to a practice range to drop these bombs, although the pilot does not remember anything about this. It is also possible that they were flying with these practice bombs on board in order to simulate the weight of real bombs as the plane would have performed differently when fully loaded than when empty.

Although the official records show that Kenneth Guy Evans was a Pilot Officer; he had only recently been promoted to Captain. The London Gazette on 14th March 1941 (click here to see this entry) lists his promotion as being given on the 8th February 1941, with seniority from the 26th January 1941. Lawrence Hugh Houghton (known as Hugh) says that he was about to be promoted to the same rank. Kenneth and Hugh were undergoing the same training and it was Hugh that was flying the plane on the outward journey that night. Kenneth was to take over flying the plane at Sharpness. He says that Kenneth was standing next to him at the time of the crash as there was only one "driving" seat in a Wellington. Charles Clarke (known as Charlie) was in the Front Gunner position, John Stuart Jones (known as Stuart) was the Navigator and Richard Wish (known as Dickie) was in the Rear Gunner position. Thomas Leonard Lever (known as Len) must have been the Wireless Operator and possibly the bomb aimer, if they were to drop any practice bombs that night. The video below gives a good view of where these positions were inside a Wellington and how much room there was for the crew.

Somehow they ended up 11 miles to the South West off course which resulted in them flying over Bristol. During the war Bristol was heavily defended because of its docks, the British Airplane Company (which amongst other things made Pegasus engines for Wellington bombers) and the airfield at Filton. These defences included balloon barrages stationed at strategic points around the city.

The weather forecast for that night was extensive low cloud over most of the UK with rain in many places. The Operations Book of 11 OTU* states that at Bristol there was no low cloud, that visibility was 4,000 yards and that there was a surface wind of 15 m.p.h. The Operations Book of 951 Balloon Squadron* states that there was a moderate easterly wind, it was cloudy and there was no lightning. Sunset was at 20:31, with civil twilight (when the sun is 6° below the horizon and is roughly when you need outside lighting to see what you're doing) at 21:09 and nautical twilight (when the sun is 12° below the horizon and you cannot make out the difference between the sea and the sky) at 21:58. The moon was 3.4 days past new and was 11% illuminated (ie it would have been a thin crescent and wouldn't have provided much extra light). The Bristol Evening Post for 30th April 1941 (see below right) shows the blackout as starting at 21:01 (9.1pm as  it was written at the time). Bearing all this information in mind it would have been dark by the time the plane flew over Bristol, there would have been no lights showing and they would have had no idea they were off course.

it was written at the time). Bearing all this information in mind it would have been dark by the time the plane flew over Bristol, there would have been no lights showing and they would have had no idea they were off course.

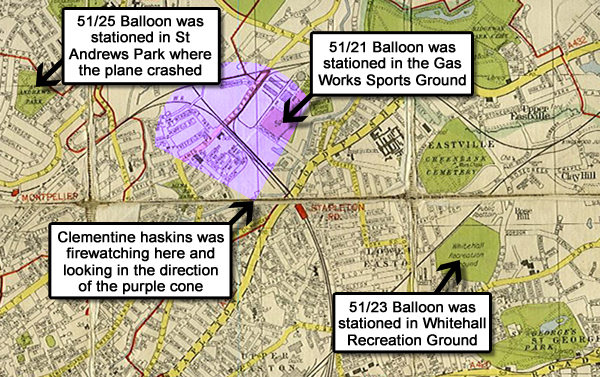

According to a letter* from the RAF to my uncle, at approximately 2150, whilst flying at about 2000 feet (training flights were not allowed to fly above 5000 feet because of the risk of encountering enemy fighters (see the notes on the official accident card*)), T2905's left wing struck a cable of a balloon barrage. Initially, because of Clementine Haskins eye witness account (see below), I believed this to be balloon barrage 51/21 from 951 Balloon Squadron, which was stationed in the Stapleton Road gasworks recreation ground near to Fishponds Road, but the 951 Balloon Squadron Operations Book (see link in the above paragraph) states that they also hit the balloon cable at site 51/23, which was stationed in the Whitehall Recreation Ground. The Operations Book states that this balloon broke away indicating that it's cable had been hit by the plane and that the explosive links in the cable had been triggered. The plane then flew on losing height and speed and clipped the cable of balloon 51/21.

The 1948 map of the area above shows where these balloons were stationed. Hover your cursor over the map to magnify it. Sorry about the quality of this map, I am still trying to find a better one! Hugh Houghton remembers the plane receiving a severe jolt. He only remembers hitting one cable, but it is likely that he was struggling so much to control the plane that he did not notice the second collision. This second collision was the one witnessed by Clementine Joan Haskins whilst she was standing on Fox Terrace fire watching, near to her father's bakers shop which was near the old stone railway bridge of Stapleton Road Station. She remembers the spotlights coming on at the nearby anti-aircraft battery at Purdown and lighting up the balloon. She saw the plane falter in mid air as it flew near to the balloon. The plane appeared to change course and fly across the railway marshalling yard in front of her towards Ashley Hill as it lost height. After the plane disappeared over the ridge there was a flash and huge explosion, and she remembers feeling the vibration where she had been standing. About half an hour later someone she was with noticed that the balloon was no longer flying. The balloon had probably been taken down in order to check the cable for damage. To listen to Clementine's memories click here* (N.B. your web browser may require you to install a flash player plug-in to use this player).

As can be seen from this diagram, balloon barrage cables were designed with explosive bolts at each end which would explode under the pressure of a plane hitting the cable. This would sever the cable at both ends and the plane would then take the ¾" steel cable with it. Parachutes would open at each end of the cable and a patch on the balloon would tear off releasing the helium and causing it to fall to the ground so that it could be re-used.

As can be seen from this diagram, balloon barrage cables were designed with explosive bolts at each end which would explode under the pressure of a plane hitting the cable. This would sever the cable at both ends and the plane would then take the ¾" steel cable with it. Parachutes would open at each end of the cable and a patch on the balloon would tear off releasing the helium and causing it to fall to the ground so that it could be re-used.

As the plane flew over the railway yard and along the railway line towards Ashley Hill one of the parachutes on the end of the cable broke off and came to rest by the side off the railway line. Len Hemmings, who lived near Mina Road in 1941, remembers hearing a plane in trouble. He walked to the end of Mina Road and up the ash path alongside the railway in the direction he had heard the plane fly. As he approached the signal box at Ashley Hill Junction* near to the Ashley Hill bridge he saw the parachute lying by the side of the track. As he climbed over the fence to investigate a signal man came out of the signal box and shouted at him to "Leave that alone, it's on railway property!" Len assumed that a member of the crew had bailed out although he saw no evidence of anyone nearby and he assumed that they had left the area by the time he had got there. He assumed that the signal man wanted the parachute for himself. There was a common misconception that parachutes were made of top quality silk that could be used to make dresses.

As the plane flew over the ridge of Ashley Hill either the plane itself or the cable it was towing behind it hit and took off the chimney of 2 Hurlingham Road

2 Hurlingham Road taken

from the Ashley Hill bridge. There is an unconfirmed report that the plane flew over a maternity home on Chesterfield Road. Miss T. Tumbridge was spending the evening with friends who lived on Chesterfield Road. They had drawn the blackout curtains because it was nearly dark. Suddenly they heard a terrific noise which sounded to them like a plane flying along the road outside. As they opened the door to investigate they were greeted by a large explosion and saw a sheet of flame in the sky from the direction of St Andrews Park. They ran to the end of Chesterfield Road and could see that the flames were coming from the park itself.

As the plane flew over Chesterfield Road it was banking towards the right and it appears to have flown along Norfolk Avenue

Norfolk Avenue looking from Chesterfield

Road towards the Park. Hugh Houghton remembers Dickie Wish shouting that he could see houses rushing past him on either side. Although many would like to believe that Hugh was aiming to put the plane down in the park in order not to crash into any houses he only remembers banking the plane towards the right and doesn't remember seeing the park until they were flying into it.

The plane flew out of the end of Norfolk Avenue and flew across Maurice Road into St Andrews Park. As it entered the park the left wing hit and took off the top of the pine tree (a European Black Pine (Pinus Nigra Nigra)) indicated in the pictures above. The damage to this tree, which stands on one side of the entrance to the park opposite the end of Norfolk Avenue, can still be seen today and is lower than the rooftops. The distance between the houses at the Maurice Road end of Norfolk Avenue is 46' 2" and the wing span of a Wellington was 86' 2"! Walking along Norfolk Avenue towards the park today and looking at the damage to the tree it seems likely that the plane hit the tree higher up and that the tree must have broke lower down, otherwise it seems impossible for the wing to have hit the tree where it broke and for the plane not to have hit any of the houses in Norfolk Avenue. The plane was still towing between 2000 and 5000 feet of ¾" steel cable. Gwyneth Browne (nee Williams) lived at 14 Maurice Road

14 Maurice Road (on the corner of Norfolk Avenue) and she remembers the cable ending up draped across the roof and around the garden gate of their house and across the road and on into the park. She remembers being in the front room at the time and hearing the plane very close to the house and wondering if she was going to die. She told me that two local children from Sommerville Road used to sleep in the cellar during the war. To begin with this had only been when the air raid sirens had sounded but soon became every night. One of them remembers that the impact of the plane hitting the ground shook the house and says their beds in the cellar were "shaken alarmingly!" Gwyneth remembers that when they came out the next day the children were confused as to why the house had been draped in cables like this. Measuring from the pine tree reveals that the fuselage and right wing of the plane must have passed over and very close to the roof of 14 Maurice Road.

Basil Thomas Stirratt

Basil Thomas Stirratt

taken June 1940, who was 18 at the time, had been to the Scala Cinema at Zetland Road that night with his then girlfriend Pamela Tiley, who was 16 at the time and who lived at 107 Sommerville Road. As he was taking Pamela home through the park they had stopped and were sitting on a bench under one of the elm trees that stood in the park at that time. He remembers hearing a plane in trouble and as he looked over his shoulder the plane came into the park from between the houses. Basil shouted "Run!" and he and Pamela ran up the path towards Pamela's home. They left the park at the entrance at the top of Maurice Road and Pamela ran home, but Basil went back to see if he could help. Pamela is now Pamela Rich and lives in Ontario, Canada. Margaret, Pamela's sister remembers Pamela coming home that night and confirmed the part played by Betty Bools (see below). Margaret died aged 85 on 27th August 2002.

As the plane continued on into the park the cable became tangled around one of the elm trees, which would have stood in the foreground of the photo above, pulling it out of the ground and in the process pulling the plane down to the ground. At this point it appears that the plane broke into two pieces, either by the impact with the ground or by the cable cutting through the fuselage. The tail end of the plane was left looking as though it were sticking out of the ground. Ken Sully was 14 in 1941 and lived in Wellington Hill West at the time. He remembers going to the park the next day. He confirmed the front of the plane was a burnt out shell. He also confirmed that the rear section, from just behind the rear observation window was separate from the front and someway behind it. He said he remembers it was stood propped up by one of the elevators with the turret in mid air and that the turret was turned inside out with what he thought were parachute lines hanging out of it.

As Basil Stirratt came back into the park he came to where the rear of the plane had come to rest and saw that the rear gunner was still in the turret and alive. He tried to get him out but the man was several feet above him. Then a lady appeared from nowhere and together they released the rear gunner from his harness. Together they got him out of the park. As they came around the corner of the park Basil remembers that there were several men lying down behind the wall. It was only then that he realized that bullets were whizzing about. By this time the plane was on fire and this must have been live ammunition they had been carrying. To listen to Basil's memories click here* (N.B. your web browser may require you to install a flash player plug-in to use this player). The lady who helped Basil was Betty Bools. She lived at 18 Maurice Road and would have been 32 at the time. Her and her brother Martin had  heard the crash and had come running to help, climbing over the wall to the park as they did so. On the left is a picture of Basil Stirrat (left) and John Penny (a local historian from Fishponds Local History Society) taken in 2002 when we met in the park and relived Basil's memories of the crash.

heard the crash and had come running to help, climbing over the wall to the park as they did so. On the left is a picture of Basil Stirrat (left) and John Penny (a local historian from Fishponds Local History Society) taken in 2002 when we met in the park and relived Basil's memories of the crash.

Martin Bools made his way to the front of the plane and rescued Sgt Hugh Houghton from the cockpit of the plane after it had come to rest against the wall of the park alongside Sommerville Road. Martin was still at home as he was waiting to be released by his firm, the British Airplane Company at Filton, so that he could join the RAF. He later did manage to join the RAF and at 24 years old was a navigator serving with 115 Squadron based at Little Snoring airfield in Norfolk. His aircraft, a Lancaster bomber, was one of 764 aircraft that attacked Berlin on the dark night of 22nd November 1943, it was one of 39 aircraft missing that night and its whereabouts have never been discovered. Martin's name is commemorated on the Runnymede Memorial in Surrey for Royal Air Force personnel with no known graves and was the third Bools brother to receive the prestigious Air Crew Europe Star for his wartime service. Three of Martin's four brothers, Charles Ronald Kernick Bools, John Stafford Bools and Geoffrey Maurice Bools, also died whilst serving with the RAF in WW2 (see http://www.cwgc.org and search for Bools)  and the four of them are commemorated in two stained glass windows, seen here on the right (these images are © Trustees of the Royal Air Force Museum - please do not reproduce without permission), that are now at the RAF museum at Hendon. Martin carried Hugh Houghton over his shoulder and Betty and Basil Stirratt carried Dickie Wish out of the park via the gate on the corner of Maurice Road and Sommerville Road. Betty remembers being stopped by the police who initially were not going to let them leave the park. They took Hugh and Dickie to the Bools house (18 Maurice Road). Betty also remembers an elm tree opposite her house was entangled in balloon cable and pulled out of the ground. Hugh Houghton doesn't remember much about the crash itself. He remembers the plane coming to rest and opening his window to see where they were and the next thing he remembers is waking up in hospital. To listen to Hugh's memories of the crash click here* (N.B. your web browser may require you to install a flash player plug-in to use this player). When Basil Stirratt returned home his father Robert sent him to bed as it was obvious he was in shock. Basil coincidentally worked at the Stapleton Road gas works where the second balloon had been stationed. He later joined the Royal Corps of Signals. After leaving the services he married Pamela Beavis. Basil died aged 84 on August 11th 2007, by which time he had three children, Carol, Jane and Nicky, four grandchildren and five great grandchildren. A tribute to Basil can be seen here. Betty Bools died aged 96 in early 2005.

and the four of them are commemorated in two stained glass windows, seen here on the right (these images are © Trustees of the Royal Air Force Museum - please do not reproduce without permission), that are now at the RAF museum at Hendon. Martin carried Hugh Houghton over his shoulder and Betty and Basil Stirratt carried Dickie Wish out of the park via the gate on the corner of Maurice Road and Sommerville Road. Betty remembers being stopped by the police who initially were not going to let them leave the park. They took Hugh and Dickie to the Bools house (18 Maurice Road). Betty also remembers an elm tree opposite her house was entangled in balloon cable and pulled out of the ground. Hugh Houghton doesn't remember much about the crash itself. He remembers the plane coming to rest and opening his window to see where they were and the next thing he remembers is waking up in hospital. To listen to Hugh's memories of the crash click here* (N.B. your web browser may require you to install a flash player plug-in to use this player). When Basil Stirratt returned home his father Robert sent him to bed as it was obvious he was in shock. Basil coincidentally worked at the Stapleton Road gas works where the second balloon had been stationed. He later joined the Royal Corps of Signals. After leaving the services he married Pamela Beavis. Basil died aged 84 on August 11th 2007, by which time he had three children, Carol, Jane and Nicky, four grandchildren and five great grandchildren. A tribute to Basil can be seen here. Betty Bools died aged 96 in early 2005.

Roger Lewis's father, Jack, was in the bed next to Hugh in the Bristol Royal Infirmary, having recently lost a leg in an accident whilst working on the Railways. Roger remembers his father telling him that Hugh had said that they were on their final training before going operational and that they had no idea that they were flying over Bristol.

David Best, aged 15 at the time, lived in Walthem Road and remembers hearing a British plane. He could tell it was British by the sound of the engines and could hear that it was in trouble. As he opened the front door to see what was happening the engine noise suddenly stopped and there was a tremendous crash. He ran to the park and along with others helped Betty, Martin and Basil get Sgt Houghton and Sgt Wish into Betty's house. He remembers the wreckage of the plane being cleared up very quickly the next day.

The front end of the plane had continued on up the hill of the park. At some point it burst into flames, possibly as fuel from the tank inside the left wing, which may have been punctured by the cable digging into it, leaked out and caught fire. Hilary O'Connor remembers her brother, Bruce Clifford Westlake

PC Bruce Clifford

Westlake, who was 19 at the time hearing the plane crash and running out of their house (1 Effingham Road, at the Chesterfield Road end) to go and help. Bruce was a probationary police officer stationed at Horfield Police Station

Horfield Police Station,

Sommerville Road on Sommerville Road. He did not come back for some time, but when he did return his cream coloured coat was black. She remembers Bruce telling her that when he got to the plane he had become annoyed that no-one seemed to be doing anything because they thought it was a German plane. He told his sister that he had gone into the plane and managed to pull Sgt Jones out. He was helped by a Sgt George Goodall of the Home Guard (who lived on Chesterfield Road) to get Sgt Jones out of the plane. Sgt Jones was taken to the Emergency First Aid Post which was in the basement of 61 Effingham Road suffering from broken bones and severe burns to his face, scalp, neck and hands. It was some time before he was stable enough to be taken by ambulance to hospital.

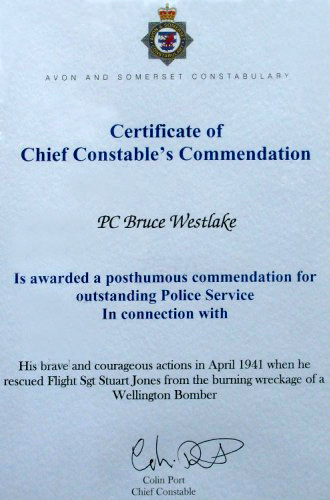

Bruce Westlake visited Sgt Jones later in the Bristol Royal Infirmary. Stuart Jones' mother, Nellie Jones, later wrote to P.C. Bruce Westlake. Click here* to see this letter and the ensuing correspondence. Bruce finished his probationary period and joined the police force later that year. In 1943 he joined the RAF and returned to the police force in 1946. Bruce had an interest in music and ran three dance bands, being a piano accordionist. He married Hazel Johns, who was expecting their daughter, Karen, when Bruce was severely injured in a road traffic accident on 5th December 1946. Karen was born one week after the accident. Sadly Bruce died in Winford Hospital on 14th January 1947. On 26th September 2009, at the ceremony to unveil a memorial to the crash in St Andrews Park, Bruce's daughter, Karen Reilley, was presented with a posthumous award

Bruce Westlake visited Sgt Jones later in the Bristol Royal Infirmary. Stuart Jones' mother, Nellie Jones, later wrote to P.C. Bruce Westlake. Click here* to see this letter and the ensuing correspondence. Bruce finished his probationary period and joined the police force later that year. In 1943 he joined the RAF and returned to the police force in 1946. Bruce had an interest in music and ran three dance bands, being a piano accordionist. He married Hazel Johns, who was expecting their daughter, Karen, when Bruce was severely injured in a road traffic accident on 5th December 1946. Karen was born one week after the accident. Sadly Bruce died in Winford Hospital on 14th January 1947. On 26th September 2009, at the ceremony to unveil a memorial to the crash in St Andrews Park, Bruce's daughter, Karen Reilley, was presented with a posthumous award for Bruce's "outstanding Police Service" by Assistant Chief Constable John Long of the Avon and Somerset Consabulary. The picture above shows Hillary (left) and Karen (right) with the award standing in front of the memorial in St Andrews Park. To see Karen receiving this award watch my video of the memorial dedication ceremony on my Memorials page (Part 3 shows the presentation of Bruce Westlake's posthumous award). Hillary was very proud to see Karen recieve this award.

for Bruce's "outstanding Police Service" by Assistant Chief Constable John Long of the Avon and Somerset Consabulary. The picture above shows Hillary (left) and Karen (right) with the award standing in front of the memorial in St Andrews Park. To see Karen receiving this award watch my video of the memorial dedication ceremony on my Memorials page (Part 3 shows the presentation of Bruce Westlake's posthumous award). Hillary was very proud to see Karen recieve this award.

Betty Bools also visited Stuart Jones in hospital over the next six months or so. She remembers him having gangrene at one point and put an appeal in the Bristol Evening Post for a mosquito net to help keep off the flies. Stuart had his left index finger amputated at this time due to the gangrene. Stuart was later admitted to Queen Victoria Hospital, East Grinstead and became part of the so called "Guinea Pig Club*".

Frederick Richard Spray

Frederick Richard Spray

(left) taken in the late 1920's showing his enthuiasm for motorcycles

(right) taken in 1955, who was 34 at the time, lived at 8 Leopold Road. He was a DIY enthuiast and was working on his fret saw when he heard the crash. He ran out of his house and into the park to see if he could help. He either helped Bruce Westlake and Sgt Goodall rescue Sgt Jones or tried to rescue Sgt Lever. Patricia Seymour, Frederick's daughter, remembers him telling her that he had ran out in his slippers and the soles of these had melted in the heat of the fire and had stuck to the tarmac in the park. Kevin Seymour, Frederick's grandson, remembers that Frederick had told him that he had gone into the plane, suggesting that it was the front end of the plane, and that he had told him that he had suffered burns to the back of his hands.

Cliff Voice, who was 16 at the time and lived on the corner of Shaldon Road and Muller Road, remembers being outside his house with his father, the Rev. Norman Voice, and hearing the plane. He then heard a bang and saw smoke in the air. His father and mother took Cliff with them in their Austin Seven car as they went to see if there was anything they could do. His mother, Daisy, was a Red Cross Nurse and attended to one of the survivors in a house in Effingham Road. He apparently could not be moved for some time. Cliff thought this was the navigator. Margaret Lowle Green (nee Davis) was 19 at the time and was a member of the area first aid team. She lived with her parents and brother and sister at 49 Effingham Road. On the night of the crash she was in the front living room of the house with her sister and mother listening to an opera of Hansel and Gretel on the radio. Her brother, Howard, who was 12 at the time, was in bed in the back living room (this was his bedroom at the time) also listening to the opera. Margaret remembers hearing a large plane flying very low and rapidly losing height. There was a loud bang and the three of them threw themselves onto the rug in front of them, knocking their heads together as they fell to the floor! She got up and ran to the Emergency First Aid Post which was at 61 Effingham Road

61 Effingham Road (taken in 2011), near to the junction of Grenville Road. She remembers that at least one airman was brought to this First Aid Post, but there was not much they could do for him as his injuries were beyond their skills. She says that a Dr Heron, who lived at 2 Leopold Road, treated the burns on the back of the man's hands before he was taken to hospital. This airman must have been Sgt Jones, as he suffered burns to the back of his hands. Margaret later visited the man in hospital. Howard Davis, Margaret's brother, went to the site of the crash with his father. He confirms that the front section of the plane came to rest against the wall of the park on Sommerville Road, about half way between Maurice Road and Melita Road and against the fence of a compound that housed the balloon barrage that was stationed in the park. He remembers seeing aviation fuel on fire as it ran down the gutter of Somerville Road. He also confirms that the plane hit and took the top off the pine tree opposite Norfolk Avenue and that an elm tree had been pulled out of the ground a bit further into the park. Elizabeth Ware was about 7 years old at the time of the crash and lived at 51 Effingham Road. She confirmed that the Emergency First Aid Post was in the basement of 61 Effingham Road. She remembers her and her younger sister, Margaret, being taken there and 'practiced on' and has fond memories of the owner of the house, a Mr Lloyd, coming downstairs when they had been bandaged and asking, "What's wrong with these children? I know the best medicine for them!" and producing sweets from his pockets for them. Elizabeth's father was a street warden and she remembers him coming home to tell her mother that a plane had crashed in the park and that he was going to help.

Mrs Markhill lived at 19 Sefton Park Road at the time of the crash. She had a baby, born in February that year, who was in a cot at the time. They had a glass door at the front of the house, which was blown in by the blast of the explosion when the plane hit the ground. She said her and her husband had heard the plane approaching and had felt as well as heard the explosion.

Alan Robins lived in Belvoir Road and was 15 at the time of the crash. He and his father were fire watchers during the war and had previously survived when their house was hit by an incendiary bomb. He remembers hearing the crash and hearing ammunition exploding. He remembers seeing the burnt out plane in the park the next day.

Harold Turner lived near the park and was a part time fireman at the time of the crash. He remembers coming home from work, changing into his fireman's uniform and going to have a nap before going on duty, which was his usual routine. He was woken by his landlady, who told him there had been a plane crash in St Andrews Park. He got on his bike and went to the park to see if he could help. He confirmed that the plane had broken into two and that the front section had come to rest against the wall of the park on Sommerville Road, near to where there had been a hut for the balloon crew stationed in the park. He recalls that there were lots of Home Guard men running around with fixed bayonets! He remembers seeing a man on a stretcher calling out for his mother, possibly Alfred Rowlands (see below) or Sgt Stuart Jones. Harold had nightmares about this for some time afterwards. Harold is not the only person to mention the Home Guard being present in the park. Sgt George Goodall, who helped Bruce Westlake rescue Sgt Jones, is refered to by Bruce as being in the Home Guard and several other people have mentioned them. The 9th Gloucestershire Battalion (City of Bristol) Home Guard had their headquarters at 99 Sommerville Road. To read more about the 9th Battalion and it's organisation in Bristol click here*. 'A' Platoon of No. 12 Battallion Gloucestershire (City of Bristol) Home Guard was stationed in the hall at Pig Sty Hill, Gloucester Road. Private 9/754 Lawrence Northam

Lawrence Northam (known as Larry)

Left:taken in 1944 - Right:taken in 2009 (known as Larry) remembers being on sentry duty that night. At 21:50 there was a loud roaring crash with a huge fire from the direction of St Andrews Park. Larry alerted the platoon and they were the first uniformed service to arrive in the park. They entered the park from the Melita Road entrance and were detailed to keep the public from getting to close to the burning plane. When the police and fire service arrived they returned to there station at Pig Sty Hill.

Rene Chambers was 21 at the time of the crash and lived with her parents in Kennington Avenue (to the north of the park). Her father, Sgt William Benjamin Dowler

Sgt William Benjamin Dowler (known as Bill)

in his Home Guard uniform taken in 1942

& Bill later in life, was in the Home Guard and was on duty that night. She remembers him returning home and being very tearful and obviously in shock. He had gone to the park to help and had tried to rescue someone from the front of the plane. He had assumed this was the pilot, but this must have been the front gunner, Charlie Clarke, as the pilot would have been further back and higher up. Bill had been driven back by the flames and had been unable to get the man out. Rene says her father had been unwell for a long time after the crash and had had nightmares for some years later. Bill died aged 75 in the 1970's.

Air Crewman 618025 Alfred George Arthur Rowlands

Alfred George

Arthur Rowlands

(known as Alf), who was 24 at the time, was one of the balloon barrage crew stationed in the park that night. He is listed in the Operations Book of 951 Balloon Squadron* as being injured. Before the war Alf had joined the merchant navy shortly before his 16th birthday in 1932 and had served as a deck boy. He served aboard the S.S. Ormonde on trips to Australia and around the Mediterranean and aboard the S.S. Durham Castle on trips to South and East Africa. He enlisted into the RAF on 17th August 1938 and was released from service on 28th October 1945. On both his Continuous Certificate of Discharge for the merchant navy and his RAF Certificate of Service and Release his surname is given as Rowlands (click here* to see these documents). On the former he has signed his surname as Rowlands, but on the latter he has signed it as Rowland. Mike Rowland, Alf's son, says that his dad would never talk about what had happened to him during the war and would change the subject if asked. His mother told him that his dad had climbed onto one of the wings of the aircraft and was attempting to rescue one of the pilots when there was an explosion which threw him to the ground. He suffered many broken bones and was badly burnt. Mike tells me that Alf's skin was blackened by the burns that he sustained and that he suffered from breathing difficulties for the rest of his life. Alf died on April 10th 1988, aged 72, from respiratory failure and chronic obstructive airways disease.

After the crash a Mr C.R.G. Davis of the Bristol Evening Post wrote to the Lord Mayor about a George Albert Clifford

George Albert Clifford, recommending him for a gallantry medal. George was a City & Marine ambulance driver and was off duty that night. Mr Davis writes that George had been near the park that night and had gone to help. He states that along with a Cpl. Rosser, who was attached to 501 Squadron of the RAF at Filton, George had attempted rescue work. This letter was referred to the police for investigation. Brian Clifford, George's eldest son, who would have been 4 years old at the time, remembers being told by his grandfather that his father had been at the crash site and had attempted to rescue one of the crew. George had earlier been presented to King George VI after rescuing a couple from a house that had collapsed. This was probably during the King and Queen's visit to Bristol on the 16th December 1940. Mr Davis also mentions George having previously rescued a man who had fallen into the Avonmouth Dock. Click here* to see transcripts of the these documents including a picture of George being presented to the King. George died of a heart attack on the 27th August 1978 aged 66.

The fire brigade Occurrence Book* states that they received a call at 21.59 and that it took them until 23.41 to bring the fire under control. It also makes mention of them having to bury some magnesium. It is unclear what this might have been. I had initially thought this might have been parts of the planes fuselage that may have caught fire, but the geodetic framework used in the construction of Wellington's was made from aluminium and not magnesium. It is more likely that this could have been magnesium flashes, which were used on bombing training exercises. These were dropped just after the bombs and lit up the target so that it could be photographed in order to prove the accuracy of the bombing run.

Captain Kenneth Evans, Charlie Clarke and Len Lever died in the crash and subsequent fire. Hugh Houghton, Stuart Jones and Dickie Wish were rescued. To find out more about each of these men click on their photo in the menu to the right hand side of this page.

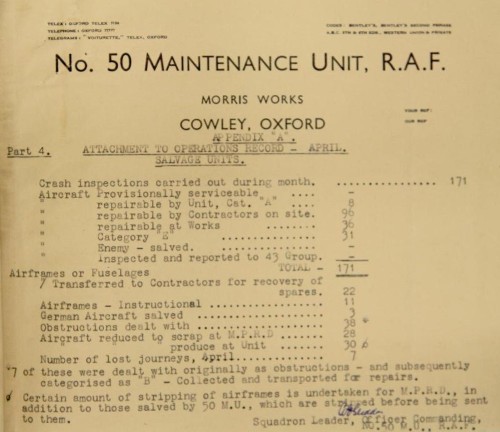

The wreckage of the plane was removed by No 50 Maintenance Unit and taken to the No.1 Metal and Produce Recovery Depot which was based at the Morris Motors factory at Cowley, Oxford, where anything useable would have been salvaged and the geodetic framework and any other metal would have been cut up, melted down and sent on to be reused to make new aircraft. To read Doreen Holly's memories of working at this facility click here* The operations book for No 50 Maintenance Unit does not record the daily activity of the unit, but it does record that 171 crashed aircraft were recovered in April 1941

Appendix A for April 1941

This book can be found at the

Pulic Records Office at Kew. Ref AIR 29/1009!

Click here to see a map created on Google Maps showing key points of interest in the story.

Click here* to listen to John Penny, from Fishponds Local History Society, being interviewed about the crash on BBC Radio Bristol on 9th March 2009 (N.B. your web browser may require you to install a flash player plug-in to use this player).

Click here* to see a list of information I am still looking for.

Wellington T2905 was one of four British aircraft brought down by balloon barrages in the Avon area in 1941. The other three were as follows (information obtained from Fishponds Local History Society (http://fishponds.org.uk/puckle.html)):-

- 21st February - Hurricane P3653 of the Filton based No.501 Fighter Squadron which collided with the cable of the balloon at Site 35/20 operated by Filton's No.935 Squadron. The aircraft crashed in a field at Patchway, about 500 yards from the Site, the pilot 903560 Sgt. D.G.Grimmet being killed.

- 22nd February - at 14.12 hrs Heinkel He 111H-3, Wnr. 3247, IG+GM of 4/KG 27 operating from Bourges in France, and on a mission to attack Parnall's Aircraft Factory at Yate, collided with the balloon cable at Site 27/29. The aircraft's port wing was torn and it crashed a little less than a mile away from the point of impact, while the balloon itself broke away. The only survivor, Ltn. Berndt Rusche, the pilot, said that prior to impacting the cable he was hit once in the port engine and at least twice in the fuselage by heavy A.A. fire and one of these hits was thought to have carried away the entire tail unit. The other crewmen - Fw. Georg Jankowaik the Wireless Operator; Gefr. Erich Steinbach the Gunner; Uffz. Heinrich de Wall the Flight Engineer; and Fw. Albert Ranke the Observer - were all killed.

- 20th March - Magister V1065 of the Service Ferry Pool collided with the cable of the balloon at Site 35/5 operated by No.935 Squadron at Filton and crashed 50 yards from the site. The pilot F/Lt. Smith based at Kemble airfield was killed.

Thank you to all the people who have contacted me and told me their part of the story and thus helped me to tell the big story of what happened to Wellington T2905.